Summer has been a bit of a lull - well, okay, a torpor. I'm doing some sewing, but not finishing much. As anyone who's ever been in my company for more than 3 minutes knows, I HATE to be hot, and my motivation to do anything drops drastically when the temps go up. I prefer to sit in the bathtub with a cold Mexican Coke, panting until September.

But I made a discovery the other day that was cool, so I figured I'd share. This is a crappy, beat to hell quilt that I bought for $5 from what I recall as an ice cream store, in Sparta, Wisconsin, while taking a lunch break from acting as a massage therapist on the Minnesota to Chicago AIDS Ride in 1997:

|

| Sorry the pictures are so dark. |

I had only wanted it, really, because we needed something to keep the sun off of our clients in the (incredibly hot, smelly) tent we were working in. But of course because it was an AIDS ride, and the AIDS quilt project was making its way around the U.S. on a pretty much continual loop by then, many of my clients naturally made this association and it triggered them to talk openly and emotionally about their friends, families, and lovers who had battled or lost their battles with HIV and AIDS. That was probably one of the most conversation-provoking sun shades I've ever used. I've always kind of loved this thing since then, even though it really is in horrible condition.

So that was 17 years ago (!!!) and I've carried it through several moves, sometimes folded for couch decoration and sometimes rolled up and stored, and currently on my bed as a nice summer weight blanket that is extremely soft and cozy because of the years of wear (which wear, incidentally, also results in me waking myself up sometimes by breathing in stray wads of fabric that get torn off of its increasingly threadbare patchwork.)

|

| Charming, but not very delicious |

I've always been idly curious about these fabrics, which are extremely random in color and print, and then are even more randomly put together in a completely unpremeditated way. But given my recent fixation on fabric and quilting I took another look at this sucker the other week, and made a few discoveries. For one, I realized that each of these pieces were sewn directly onto a light pink backing fabric with a machine, overlapping each other until they were big enough to make a large square, and then the squares were sewn together; then that top was sewn to large, solid light pink pieced background without batting and those two layers were sewn together loosely by hand with a long, messy running stitch that can barely even be called quilting - it really looks like basting. In other words, this was one of the most thrifty kinds of quilts: it used entire scraps, without altering them after they were leftover from whatever other sewing project was going on, and regardless of their funky shapes or the color combinations; and then it was slapped together in an extremely utilitarian way, probably for exactly the reason I'm using it, a summer blanket, given the lack of batting. (Strictly speaking, it's not a "quilt" because quilts are traditionally top, batting, and backing; but "quilts" is easier to type than "summer blankets", so nyah.) Part of the reason I like quilting is this heritage of "use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without", which was a housewifey mantra during the Depression and WWII, but is a theme running through American utility quilts from colonial days' paper-stuffed quilts on. So this quilt I've been toting around for nigh on two decades is suddenly even cooler to me, because it is a product of that frame of mind that I'm just now coming to really appreciate.

Recently I got this book by Eileen Jahnke Trestain called "Dating Fabric: A Color Guide 1800-1960," which is a helpful introduction to the colors, patterns, materials, weaves, and uses for fabrics of different eras in the U.S. I had suspected my quilt was probably from the 50s or so, just because of the candy pinks that dominate it, but per this book, that cadet blue, the "double pink" fabrics (those with two shades of pink printed in two passes), the plaid fabric with differing types of thread (silk or coarser cotton cords) and the multi-colored prints mean this quilt may be more like 40s era, and most of these fabrics are likely feedsack prints. (Quilts are dated from the most recent fabric used, and it's of course possible this quilt was made from fabrics that were already old when it was put together.)

|

| You can see the overlapping where the pieces were just slapped one atop the other. |

Feedsack quilts are another thrifty part of quilting and sewing history, as well as being a brilliant marketing coup, and an indicator of a sea change in American economic policy, all rolled into one colorful calico bundle. Far more scholarly folks than I have already gone to great lengths to research this thoroughly (and eBay has a nice summary), but the gist of it is that fabric bags replaced bulky, hard-to-transport barrels and boxes, to package and sell bulk animal feed, grains, sugar, flour, coffee, and other household comestibles, in the mid-19th century. These sacks were recycled into clothing and blankets by clever housewives; and bulk manufacturers figured out that husbands may be sent off to buy more product if that product were wrapped in something specifically desired by the seamstress at home, something perhaps even pretty enough to make a dress. Suddenly, a product that was otherwise a commodity had, with the addition of a little intellectual property in the print design process, a big value-add qualitative differentiation, essentially becoming two, two, TWO products in one! This new-found marketing ploy, plus the increasing value placed on thriftiness and economizing, escalated to a Depression- and WWII-era boom in the use of feed sacks for every damn thing under the sun: dresses and shirts, but also hand towels, aprons, diapers, quilt backings, nightgowns, undies, whatever.

So I was intrigued by this whole business of feedsack quilts and was hoping to find actual samples of my fabrics in order to date them, maybe in some catalog online or in this Color Guide book…until I learned that there were literally thousands of these prints created, and it does not appear that anyone has yet created a catalog of these prints that I have found. Trestain's book, however, did give me other clues about what I was looking at. For instance, chemical dyes were taking over for dyes made of natural materials around the 20s and 30s, so colors were less likely to bleed away as they did in colonial and Civil War-era quilts. (Yet another interesting historical economic side-note I'd like to explore in greater depth some day: a deep red made for centuries with madder root was replaced in the early 1800s by a revolutionary but expensive synthesized version of the longer-lasting of two compounds found in madder; and after one of the necessary ingredients for this process was discovered to be a cheap by-product of coal tar in 1871, the market for madder collapsed virtually overnight.) My quilt is plenty faded and battered to hell, but upon closer examination, I could see that where some prints had been protected by other layers of fabric that had eventually be worn or torn away, the 20th century dyed colors were still pretty vivid, in a few cases strikingly so, much like you'd expect fabrics that were NOT 70 years old to behave:

|

| A crazy hot pink and a deep navy were hidden under another fragment: the red check still pops. |

|

| You can also see the hand-stitching on this shot, going right through the middle, top to bottom. |

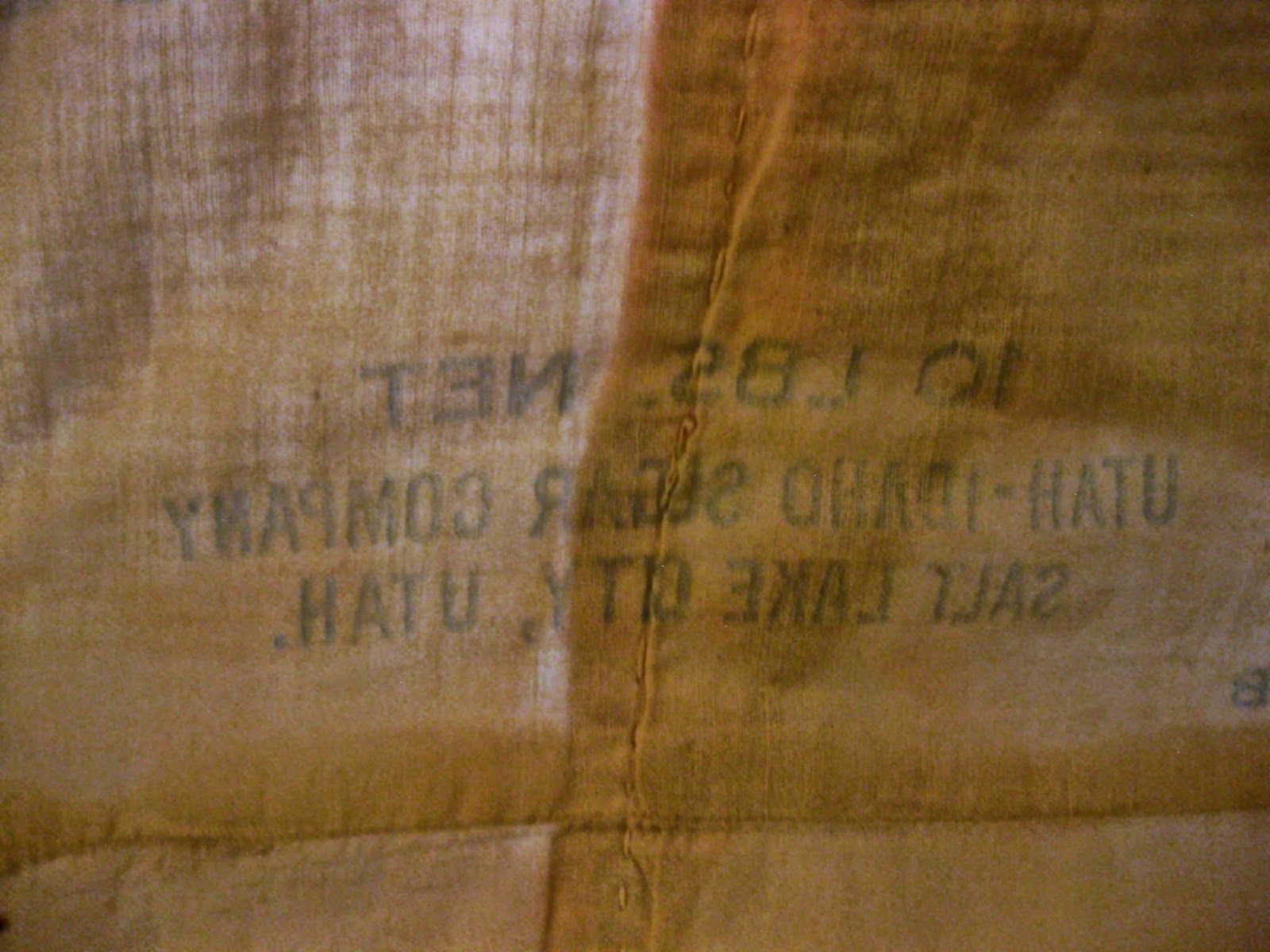

But I think the coolest part of my re-discovery of this old friend was a chance glimpse, while I was folding it up with a light behind it, of writing turned to the inside-wrongside of the quilt, which I'd never noticed before despite inspecting the top fabrics numerous times. Before this fabric was used as quilt backing, it was sugar sacks - best I can figure, there are three different feedsacks used to create the back, all of which appear to be 10 lb bags of sugar from different manufacturers: the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company in Salt Lake, the American Crystal Sugar Company in Mason City, Iowa, and the Amalgamated Sugar Company in Ogden, Utah. I'm assuming this means that some or most of the top fabrics are also feedsacks.

|

| I reversed this one so I could read it more clearly. That logo is still in use today. |

|

| "A Product of American Farms" |

|

| "The Amalgamated Sugar Company, Ogden Utah, Idaho Factories Twin Falls, Burley, and Rupert" |

Now, I don't know why I got so excited about this: in 1942, 3 million women and children were thought to be wearing feedsack clothing, so it's not like these were a rarity (folks still sell them on eBay and flea markets and such - I just bought one for $10 because it's the same as the Crystal Sugar one above. Exciting!). I think it was just the idea that I've been sitting under these sacks on my couch for TWO DECADES, with no idea what they were - which seems to me to be the very definition of a utilitarian hand-made item, and I kind of hope all of my quilts end up threadbare and well-used, and that someone 50 years from now will be wondering at all of my sloppy stitching and unevenly matched seams, or the source of my peculiar and dated color sense. I encourage any of my quilt-recievers to abuse the hell out of your quilt, so the task of my future judges is all the more difficult.

These feedsacks also sent me down the rabbit hole investigating the sugar companies in question, looking for clues about the time period during which these bags were made. But MAN, the history of sugar production in the Americas is a FASCINATING jaunt down our nation's economic policy trials and errors. Sugar was investigated as a monopoly after the Sherman Act in 1890, since the American Sugar Refining Company owned pert near all sugar production in the States, as well as interests in the Caribbean. The whole decision was slowly reversed in increments by later cases, but Big Sugar had already fragmented into little sugar cubes, including a huge swath of beet sugar farms owned by the Morman church as this interesting little book describes. It was in part this government mandated fragmentation that led sugar manufacturers to jump aboard the feedsack bandwagon - if they had to be a commodity, they were going to have to distinguish themselves for their market, just like grain and flour and coffee had to. What better way to do that than via a charming calico? Though it does make me wonder whether the feedsack backing fabric of my quilt was actually pink, or if some of the red fabrics bled over the years, or if its creator actively dyed the fabric? Seems an unlikely color to get your sugar delivered in, but then, I wouldn't expect my sugar to be delivered in plaid, but apparently that happened too.

Big Sugar was further divided by the difference between beet sugar production, which refining process was pretty long and labor intensive, and cane sugar production, which requires a very specific climate so is limited geographically but easier and cheaper to produce (hence you hear about "C&H Sugar/ Pure Cane Sugar" today, a product of California and Hawaii, and not "Pure Beet Sugar from Twin Falls, Idaho".) Labor used to be easier to come by, of course, but after slaves revolts in the Caribbean and the end of gang-pressed Japanese and Mexican foreign nationals interned on sugar camps during WW2, cane sugar has the majority of market because it requires less labor.

|

| Bag ladies. This picture was originally from National Geographic in 1947, but I swiped it from the Etsy Blog here. |

Big Sugar was further divided by the difference between beet sugar production, which refining process was pretty long and labor intensive, and cane sugar production, which requires a very specific climate so is limited geographically but easier and cheaper to produce (hence you hear about "C&H Sugar/ Pure Cane Sugar" today, a product of California and Hawaii, and not "Pure Beet Sugar from Twin Falls, Idaho".) Labor used to be easier to come by, of course, but after slaves revolts in the Caribbean and the end of gang-pressed Japanese and Mexican foreign nationals interned on sugar camps during WW2, cane sugar has the majority of market because it requires less labor.

But U.S. protectionism for domestic sugar production is actually alive and well, and results in us paying 3 times as much as the rest of the world for sugar. And then combined with U.S. corn subsidies, the overpricing of sugar leads directly to an increased use of high fructose corn syrup as a sweetener by U.S. manufacturing, which is both the reason for Mexican Coke and also clearly has far-reaching health ramifications for the United States - a plague that we have brought upon ourselves. Not to mention that it makes sugar ethanol an impractical solution for green energy initiatives which again must defer to corn ethanol because of cost. Economics 101 will always favor free trade in this context, which would drive down the price of sugar because of how cheaply cane is grown and processed in other countries, and loss of U.S. jobs would certainly occur. But I can't help thinking that protectionism is the most severe form of being penny-wise and pound foolish, and as such must be regarded with suspicion at a minimum. It is a most un-thrifty way of doing things, as I believe my thrifty mystery quilt maker would agree. Of course, she probably wouldn't be too keen on sending our sugar jobs to India, either, but at least her feedsacks would be cheaper.

|

| Ahhhhhh….Coca-Cola es lo |

Man, I love Mexican Coke. I hear they're considering changing their formula to HFCS too, which would totally suck.

Anyway, I still don't really know when I should date this quilt to - some of the fabrics could have been added later, but that means the back would also have to have been added later, since the overlapping machine patchwork style means that I can see which were the last fabrics added and that those stitches didn't go through both layers. I'm leaning towards the late 40s for several reasons: one, 10 lb bags of sugar weren't produced by the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company until 1938. Two, that cadet blue is pretty clearly pegged to the 40s in the Color Guide. Three, the plaids in here strike me as more late 40s/early 50s (think all of the shirts in Leave it To Beaver) than anytime before or after that. Four, the Burley factory of the Amalgamated Sugar Company, mentioned on one of my backing sacks, closed in 1948 (it never got back off the ground after switching to potato dehydration for the War). And finally, per the Color Guide, use of feedsacks as fabric petered out even in rural America by the 60s, because the even cheaper paper bags developed in the 50s were becoming more common for the original purpose of the feedsacks - i.e, to sack feed; as well as the post-war Shiny New Chrome snobbery that turned its nose up at the use of the humble feedsack. Now that we were rich and prosperous again after years of privation, no self-respecting housewife would be caught dead in feedsack couture - probably, not even in Sparta, Wisconsin, which may well have been the last bastion of thrifty.

Which is a pity, really, because it seems to me that as a society, we could use a return to the "use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without" sentiment of old. Maybe when this quilt is even more used up, like down to individual summer blanket molecules, I will repurpose it again in one of my quilts, just to confuse the hell out of anyone who might be sitting on her space-age flying couch with Mexican Coke in 2060, wondering how a 1940s feedsack got into a quilt that was clearly made in the early 21st century. I hope, like me, she relishes the challenge of figuring it out.

No comments:

Post a Comment